I have to admit that it was with trembling fingers that I pressed send on this post two weeks ago.

I don’t know why I was nervous particularly—mental health has become a frequent discussion in my writing communities, some of my closest friends have struggled with it, and many of you have been writing to me for years asking me to please tackle this subject—but I know that on a personal level, especially where I come from (India), mental health is still very much a taboo subject.

Over the three days that followed the publication of that post, my phone and Inbox filled up with likes, hearts, texts, messages upon messages of support, of thanks, of understanding.

I feel loved and cared for. I cannot tell you how much that has meant to me. Thank you.

I am still going through my Inbox and responding to the emails, but one of the things that stood out most for me was something I hear from new writers all the time, in a different context, which is this:

“My parents/siblings/close friends don’t get it. They just don’t. And I don’t know what to do.”

The lack of understanding, whether regarding mental illness or a writing career, comes in many forms, but it is usually cloaked in some sort of useless advice. “You should try walking,” I was told after my post detailing more than two decades of depression. I wanted to write back and say, “Walking! Thank you so much for suggesting that. I’ve had depression since I was 12 but I would NEVER have thought about walking. I’ll start tomorrow and be cured by next week!” But I didn’t. I thanked the person for thinking of me and went on my merry way.

You know how it goes with the writing, too. The well-meaning aunt who hears you have a book out and says, “Why don’t you go on Oprah?” You want to say, oh yeah, slipped my mind. I’ll call her now. Or when you write an article for a local publication and a neighbor will say, “You know, CNN runs news stories.” You think?

Fifteen years ago, when I was a new writer, comments like this pissed me off. Five years into my career, they just annoyed me. Now, I brush them off without much thought and move on.

Because what I’ve learned is this: People don’t know what they don’t know.

They don’t say these things out of spite or to annoy you, but because they want to say something and they often have no idea what to say. Of course, it would be nice if people would just shut up about the things they don’t know anything about, but they don’t and you can either walk through life getting extremely triggered and agitated by random comments from people you see once in ten years at a high school reunion or smile and then go talk to someone who does understand.

When writers tell me their families don’t understand their writing dreams, I tell them one thing only: Your family cannot understand your dreams because they are YOUR dreams. It is very difficult for people, no matter how much they love you, to feel as excited or inspired by your dreams as you are. That is why these are your dreams and not theirs.

The best thing you can do is go live your dream and hope that they will someday see why it mattered. The worst thing you can do is spend your entire life trying to convince them of the validity of it.

You don’t need their approval. You don’t need anyone’s approval.

Here’s the thing: After a certain age, your life becomes your responsibility. You can’t blame a childhood, a parent, or a sibling for what you choose to do after you become an adult.

They may or may not understand. Thank them if they do, be grateful. But if they don’t, do it anyway.

In this amazing interview, Elizabeth Gilbert talks about how even though her parents instilled a sense of confidence and creativity in her, they were not perfect people (who is?), and so she did not learn honesty and forgiveness from her family. She couldn’t, she says. Their parents didn’t teach it to them, and so they couldn’t teach it to her.

“You can’t blame people for not giving you what they don’t have,” she says, in a statement that is now taped up to my wall.

So if she wanted to learn about honesty and forgiveness, she had to go out in the world and learn it for herself. Because there is no rulebook in life that says that our parents must be our only teachers, that if we haven’t learned something from our families, we can’t learn it elsewhere.

In fact, we must. That is what growth is.

My father taught me generosity. He taught me how to dream big dreams, to have ambition, and instilled in me the self confidence and belief that I could achieve whatever I wanted. That no matter whether I became a writer, an accountant or a circus clown, I would succeed. My mother is the embodiment of patience, grace, of nobility. My mother has a quiet strength about her that many people perceive as weakness. But when all is falling around her, she is a pillar of strength. She is the person we all turn to when we find ourselves in pain. My mother taught me how to be strong.

My parents were, however, born in a culture that values outward success and appearances over honesty and kindness. My father, an extremely honest man, has repeatedly struggled between embracing exactly who he is and protecting his family from the opinions of the outside world. People have not always appreciated his honesty, have taken advantage of it, in fact.

I have clearly inherited this trait. And that I’m a writer mans that I practice it not only in my daily life, but by sending out emails about my mental health that end up getting seen by thousands of people and that invite opinions about me and my life that may or may not be accurate.

I have received several emails and comments from people telling me I was brave for sharing what I did because that level of honesty is still rare in our culture.

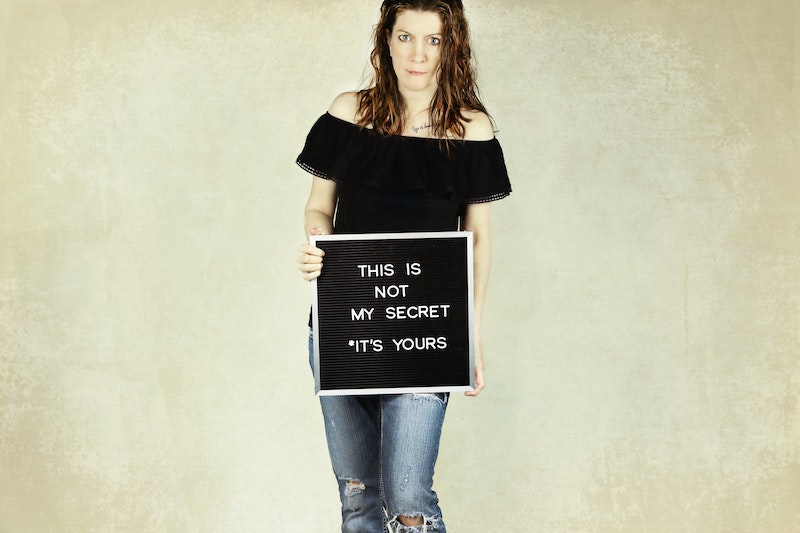

When as writers we do share personal things, we are often shamed for doing so.

I have been shamed in the past. And I have had to learn, like Liz Gilbert says in that interview, by sitting at the feet of the masters and saying, “Teach me. Teach me how to honestly speak my truth with love and kindness. Teach me how to share my story without sugar coating it for people who do not care to understand. Teach me how to not feel shame in doing so.”

I am a writer. My job is to tell the truth as I understand it. Every day, I try to do my job better, be a better writer, be a more honest storyteller.

And so must you.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a journalist, a novelist, a feature writer, or a poet.

There is honor in speaking the truth, even when the truth is uncomfortable. Especially when the truth is uncomfortable.

There is no shame in showing the world who you truly are.

There is no person in the world whose opinion of you is more important than your opinion of you.

There are people who will hate you, deliberately misunderstand you. Do not write for them. Write for the people who love you.

Tell your truth, unapologetically.

That’s your job.

Do your job.